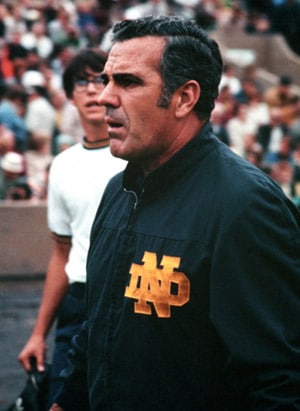

The following is an excerpt from best selling author Jim Dent’s latest book – “Resurrection: The Miracle Season That Saved Notre Dame.” The book chronicles Ara Parseghian’s first season as the head coach of the Fighting Irish and is available for purchase, along with the DVD movie “Echoes Awakened”.

Chapter 14: Disaster

Ara Parseghian sprinted toward his fallen quarterback as calm turned to chaos on the practice field.

Seconds earlier, Huarte had been driven into the ground by an onrushing lineman. Notre Dame’s future now lay in a broken pile.

Down on both knees, Parseghian whispered, “John, are you okay?”

“I don’t know yet, Coach.”

It had happened in the blink of an eye. Huarte glided back into the pocket, showing his normal poise, and was preparing to fire the rock to Jack Snow when—bam!

This scene was difficult to fathom. Parseghian knew in an instant that he should have provided better protection for his quarterback. Red jerseys signifying “no contact” were normally reserved for injured players. Huarte was not wearing a red jersey, and Parseghian now regretted it. His greatest hope for the 1964 season was now laid out on the ground.

The defensive lineman who dropped the hammer on Huarte was Harry Long, a hard-nosed kid from the west side of Chicago and a highly recruited player from Fenwick High School. Long was like Rassas—undersized for his position and underrated by all. He stood 6’ and weighed only 200 pounds. He was always hustling to overcome what could be perceived as a shortage of talent. In plowing through the line and sacking the quarterback, he was trying to show the coaches that he deserved to play in 1964, but he exacerbated the situation by turning Huarte upside down and corkscrewing his shoulder into the dirt. At the moment of impact, Huarte felt something pop. Offensive line coach Dave Hurd ran toward Long and grabbed his jersey. “What the hell do you think you are doing?” he yelled. “This man is our starting quarterback.”

Long had barely gotten out “Sorry, Coach—” when Johnny Ray came running from the other direction.

“Get your hands off my player,” he yelled. “This kid is just doing his job.” Ironically, Ray and Hurd were friends. Hurd was on Ray’s coaching staff back at John Carroll University. Nevertheless, Ray did not like anyone trespassing into his territory.

Seconds later, Parseghian roared in from the side and yelled, “Both of you coaches stop it. I’ll handle this.”

By that time, Parseghian and the entire team had encircled Huarte. Then he slowly got to his feet.

“I think I’m all right, Coach,” he said, “but I think I’d better go to the locker room. I don’t think I can throw the ball anymore.”

The stabbing pain was centered in the right throwing shoulder. Huarte now walked slowly to the locker room, his right arm numb, his heart stuck in his throat.

Huarte removed his jersey and shoulder pads and took a seat on the training table. “I’ve never felt anything like it,” he told the team trainers. “I mean, I couldn’t go out there and throw the football right now, but I really don’t know if I’m hurt that bad.”

Only a week remained until the Old-Timers Game that would pit the alumni footballers against the current players. Spring football would end that day. One more lousy week and John Huarte would have been working out in shorts and a T-shirt, but here he was, sitting slump-shouldered on the training table. Phone calls were being placed to orthopedic specialists all over South Bend.

Over the next few days, Huarte would be examined by three doctors. Each one took X-rays and were quick to deliver the bad news. He would need surgery, and that would mean no football in 1964. His collegiate career was over. Huarte finally accepted his fate and decided it was time to tell Parseghian. Early one morning, he called the coach at his office.

“Coach, I’m going to have surgery and that means my football career is over. I’m sorry.”

In a loud voice, Parseghian said, “No! Hold on, John. Don’t do anything. You can call your parents if you like, but Tom Pagna will come by and pick you up in the morning. He’ll take you to Chicago to see another doctor. It’s a guy I know. I trust him.”

Parseghian’s voice sounded panicky. Huarte did not know what to think. Did the coach value his talent that much, or was this an attempt to put a Band-Aid on a serious injury?

Parseghian made an appointment with Dr. Dick Cronin in Chicago and then arranged for Pagna to drive Huarte the next morning. An hour before leaving on the trip, Pagna got a second call from Parseghian.

“Tom, this is pretty serious stuff,” he said. “I don’t want John to play next season if he’s not physically able to, but if there is any way John can play, we need him. You know that as well as I do. If John can’t play, we’re hurting. We’ll be going with Sandy Bonvechio. Who would you rather have at quarterback—John Huarte or Sandy Bonvechio? I think that you know the answer. We need John Huarte this season.”

That morning, Pagna and Huarte rode mostly in silence the ninety miles to Chicago. Getting a decent conversation out of Huarte was like prying rosary beads away from a nun. Anxiety surrounding the injury caused him to retreat further inside himself. All of this was confusing to Huarte. Just a few months ago, no one could have cared less if he walked away and never came back. Instead, here he was, being treated like the second coming of Paul Hornung.

As the car rolled along the highway in silence, Huarte knew in his heart the coaches were only trying to salvage his final season—his only season, really. A surgically repaired right shoulder would end his playing days. Surgery would kill his last hope of accomplishing what he thought he was capable of—leading a team to a possible championship. Huarte knew that he could make this happen. This was his one and only chance—his last chance. It was like being promised the last dance of the night with the most beautiful woman in the ballroom, only to reach for her as the music stopped.

In reality, the injury did not hurt that much. Of the two possible shoulder separations, this was less severe, and it would heal faster. The separation had occurred where the collarbone met the shoulder joint. There was a chance he would fully recover without surgery. Then again, he might lose much of his velocity and accuracy. At the moment, he knew he could not fling a ball more than five feet.

Huarte and Pagna arrived at the offices of Dr. Cronin, and the quarterback took a seat on the examining table. Dr. Cronin felt the shoulder, turned it, twisted it, and probed it with his fingers. Huarte felt more depressed than ever. He was certain that Dr. Cronin’s opinion would be the same as the others—an operation to fix the separation.

Cronin took X-rays of the shoulder and returned to the examining room about thirty minutes later. Holding up an X-ray to the light and putting on his glasses, he seemed to be checking every detail. He cleared his throat.

“John, I had this exact injury when I was playing football,” the doctor said. “There is no question in my mind . . .”

Cronin paused and looked at the X-ray again. Huarte felt that bad news was coming.

“There is no question in my mind that I wouldn’t let anyone touch this shoulder. You don’t need surgery. Time is a great healer.”

Huarte jerked forward off the table and almost fell face-first. Blood rushed to his head, he coughed, and his face was now pale.

“What’s the matter?” the doctor said. “You don’t seem well.”

Huarte took a deep breath and exhaled. “I’m ok, doc. What you said caught me so off guard that I almost fainted. I never expected you to say that.”

Dr. Cronin handed him a piece of paper with suggestions on how to rehabilitate the shoulder.

“What I suggest at first is a lot of swimming,” he said. “It will strengthen the shoulder a lot. As you start to feel better, do more swimming. Don’t start throwing the football for a few weeks. Start gradually and then build up. If you have any problems, or any questions, I want you to call me.”

Huarte wiped perspiration from his brow.

“One more thing,” the doctor said. “The worst thing that might happen is that you’ll get a knot on that shoulder. Don’t worry about it. The knot means nothing.”

Huarte took another deep breath. “This is the best news I’ve ever heard in my whole life. Jack Snow and I have been talking about staying in South Bend for the summer to work out. I’ll take it slow. I’ll be ready for the season.”

Pagna smiled broadly and clapped his hands twice.

“Come on, baby,” he said. “Let me buy you a big ol’ steak.”

An hour later, at Big Bill’s Steakhouse inside the Loop, the two sawed into T-bone steaks large enough to cover their entire plates. The sudden sense of relief brought a smile to Huarte’s face. It was the first time Pagna had seen signs of happiness from his young quarterback.

“John, you know that everything is going to be all right,” Pagna said.

“I know, Coach. It just seems that everything has gone wrong for me since I got to Notre Dame. Until about an hour ago, I thought I was through with football. I’ve been up and down, and all around.”

Pagna smiled a knowing smile.

“Look, I haven’t been around Notre Dame the last three years, but I know this place has been pretty crazy.”

“Crazy is not the word,” Huarte said. “Chaos might work better.”

“They wouldn’t let you play.”

“Ah, they would let me in occasionally. I’d play one minute and be gone the next. Coach Devore said I was going to start against Michigan State. Then they pulled the rug out from under me.”

“The coaching wasn’t very good.”

Huarte dropped his fork and his eyes met Pagna’s.

“Look,” Huarte said. “Hughie Devore was a good guy. He had a big heart. He just didn’t know what he was doing. I felt sorry for the guy, if you can believe that. He took the head coaching job because Notre Dame needed somebody. He felt obligated.”

“So what went wrong?”

“Nobody was behind him. The coaches weren’t behind him. The players weren’t behind him, and I doubt the administration was behind him, either.”

“And he didn’t treat you very well.”

“Hughie had a lot on his plate. He was trying to run the same offense that Kuharich left behind, and I didn’t fit very well in that offense.”

“Ever think about quitting?”

Huarte smiled. “It was tough, but not really. I had a year left. So why not ride it out?”

Pagna placed his knife and fork on the table. The happy-go-lucky face turned sincere.

“Now, look, John. What if I told you that your confidence is shot? I’m not saying it’s your fault, but this whole Notre Dame thing hasn’t been good for you.”

Huarte stared at his plate.

“There was only one coach at Notre Dame that ever talked to me, and his name was Don Dahl,” he said. “And they fired him. I never sat down and had a conversation with Kuharich, and Hughie, you know, was always in a different world.”

Pagna cleared his throat. “You can talk to me any time you like. You can talk to Ara any time you like. Let me tell you something, John. We believe in you. We just need you to start believing in yourself.”

“That might not happen overnight, but I’ll try.”

On the ride back to South Bend, they talked like father and son. Huarte noticed that his shoulder did not even hurt anymore. When Pagna dropped him at the dorm, he felt a rush of energy—as if he were starting over.

“Take it slow, John,” Pagna said, “and when you’re ready to start throwing the rock, let me know.”

Huarte waved and said, “I will, Coach.”

That night, Pagna walked into Parseghian’s office. He was smiling.

“The shoulder is going to be fine,” Pagna said. “No surgery.”

Parseghian jumped straight up and clapped. This time, though, he did not touch his toes.

“I had a feeling,” Parseghian said. “While you were gone, I said a Hail Mary. Or two.”

“John and I had a great talk on the trip,” Pagna said, “but I think it’s time you call him in. Sit him down. Tell him how you feel.”

Parseghian calmly placed his hands on the desk. “I will do it tomorrow.”

There was a light knock on the door the next morning and Parseghian said, “Come in.”

Huarte walked in slowly and took the chair in front of the desk.

“John, they tell me that your shoulder is going to be okay. Do you feel that way?”

“Actually, Coach, it doesn’t even hurt that much anymore.”

With a furrowed brow, Parseghian said, “And the doctor told you to take it slow. I know you will.”

“I will do some swimming. When it feels right, I’ll start throwing the rock again.”

Parseghian stood, walked to the side of the desk, and sat on it. He was now just a few feet from Huarte.

“John, I gotta tell you. I have been around you only a few months, but I already see a lot of potential in you.”

Huarte smiled and looked down.

“Here’s a story that I don’t tell a lot of people,” Parseghian said. “Did you know that I am the only coach to compile a winning record at Northwestern? That’s right. Bet you didn’t know that in 1962 I coached Northwestern to the top of the polls. That’s right. And we only suited up thirty-two players that year. We lost a couple of games and didn’t get to go to the Rose Bowl, but we had a great season.

“Do you know what Northwestern said to me at the end of the 1962 season? They said they weren’t going to renew my contract. John, that really hurt. It told me that they didn’t want me anymore. I didn’t understand why, but it really did hurt. I know what you’ve been through, son. I went through the same thing. I know how it feels. Northwestern basically ran me out of town, and I felt like I did a good job.

“You haven’t been treated fairly, either, John. Your Notre Dame experience hasn’t been the greatest in the world, but you need to know that I’m going to give you every opportunity to excel. I think your time has come. If you get well—and I think you will—I want you to lead the team next season. What do you think about that?”

“I think I can do it,” Huarte said softly. “Thanks to you and Coach Pagna, I’m feeling pretty good about things. Finally.”

The two stood and shook hands.

“Here’s to a new beginning,” Parseghian said.

This has been an excerpt from best selling author Jim Dent’s latest book – “Resurrection: The Miracle Season That Saved Notre Dame.” The book chronicles Ara Parseghian’s first season as the head coach of the Fighting Irish and is available for purchase, along with the DVD movie “Echoes Awakened”.

All of the above is validated by the championship caliber season the entire team had, with Huarte’s outstanding participation. One of the great stories of greatness on the field, and great thinking from the coaches.