1965 had ended not with a bang, but a whimper. In November, Michigan State had come into South Bend and held the Irish to -12 yards on the ground, with just 24 yards passing for a TOTAL OFFENSE OF JUST 12 YARDS. The Spartans controlled the game for a 12-3 win. Then the Irish flew to Miami and left with a scoreless tie against Miami. The taste of ashes was in the mouths of Irish fans.

The Struggle of the Parseghian/Pagna Offense

What of the vaunted Parseghian/Pagna offense? Three points in the last eight quarters.

It was not thunder but heads that were shaking in Michiana. However, a trinity of coaches in the football coaching offices spent no time fretting and a lot of time preparing for the 1966 season.

Rebuilding for 1966: Spring Practice and the Quarterback Race

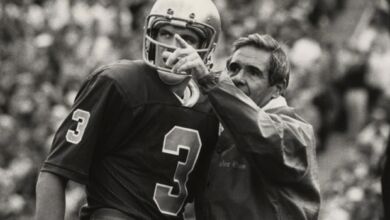

Ara Raoul Parseghian, entering his third year, was burning with passion and belief in his players. The courageous, noble Bill Zloch had quarterbacked the Irish in ’65, but Bill just could not pass the ball. Ara and Pagna had recruited four quarterbacks for the ’65 season, but freshmen were ineligible, so Coley O’Brien and Terry Hanratty were restricted to the Cartier practice field. They had brought in two lanky receivers, Kurt Heneghan from the Pacific Northwest, and Jim Seymour from Royal Oak, Michigan.

Tom Pagna, Ara’s offensive alter ego, proud of the running assets he had marshaled, just needed a modest passing attack to create space for his rushers, like Nick Eddy, Larry Conjar, and Rocky Bleier. Pagna was itching to get back to work for spring practice, anxious to get his young quarterbacks and receivers ready for varsity action.

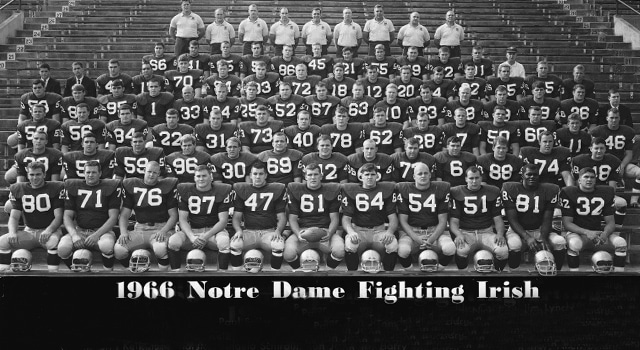

Defensive Strength: Johnny Ray’s Fierce Unit

Johnny Ray was the defensive coordinator. Johnny was an ex-Marine, and we were then closer to WWII and what we can call the “Junction, Texas” mentality in coaching and player empowerment and satisfaction. Johnny Ray was not inclined to mention “hydration” as a key to great defense. Alan Page once remarked about Ray that he was the meanest white man Page had ever met. Ray liked what he saw on his defense.

The front line was Alan Page, Kevin Hardy, Pete Duranko, and Tom Rhoads. Pete Duranko was from Johnstown, PA, no tropical paradise. Duranko played with a coal miner’s/steel mill worker’s intensity, worthy of Johnstown. Alan Page was magnificent, on his way to success in the NFL, including an NFL MVP in 1971. Kevin Hardy was one of the greatest athletes ever to play at Notre Dame: football, baseball, basketball, and golf. He did not play with the ferocity of Duranko and Page, but his natural gifts more than made up for it. Rhoads was the lone mere mortal on the DL, but a tough kid, solid tackler, fundamentally sound. There may have been better front fours that have played in the glorious history of college football. Or not.

The linebackers were stout. All-American candidate Jim Lynch was the captain and leader, buttressed by John Pergine, John Horney, Mike Martin, and Mike McGill. They gathered up the fragments from the destruction wrought by the front four. It was 1966 and the 4-4-3 defense was almost universally in use. The back line was Tom Smithberger, diminutive Tom O’Leary, and Tom Schoen, dangerous as a punt returner.

Offensive Returnees and Open Positions

The offense was loaded with returnees at nine positions. Don Gmitter, Conjar’s buddy and soulmate from Pennsylvania (Gmitter from Pittsburgh, Conjar from Harrisburg), was the tight end. Paul Seiler and Tom Regner manned the left side, flanking center George Goeddeke, as wild a character as ever roamed or prowled the Notre Dame campus. Dick Swatland was the right guard, and Bob Kuechenberg was the right tackle.

The backfield of Larry Conjar, he of the four TDs in the romp over Southern Cal in the rain and mud in ’65, Nick Eddy, the swift Californian, and Rocky Bleier, the all-purpose Theo Riddick of his day, was intact.

The open positions were at quarterback and wide receiver. Seymour moved past Heneghan by a margin in the spring. O’Brien and Hanratty were in a near-dead heat at QB, and as spring ended, O’Brien had a slight edge in the clubhouse.

Notre Dame’s Daunting 1966 Schedule

Purdue was coming in for the home opener. The Boilermakers had TWO legitimate Heisman contenders, senior quarterback Bob Griese and lightning-fast back Leroy “Nursey” Keyes, a great offensive weapon who was brought in on defense in key downs.

The Irish had a brutal finish to the 1966 schedule, having to travel to East Lansing to confront the mighty Spartans and then go to the LA Coliseum to face Rose Bowl contender USC. It was the scene of the 1964 nightmare, and the melody lingered on. Fear, not facts, dominated the mindset of the fan community. In pre-fall practice, although this was kept under wraps until much later, not only did Hanratty win the job, but Parseghian and Pagna were astounded at the efficiency and range of the sophomore connection, Hanratty to Seymour. It seemed heretical to think it, but they seemed more explosive, more dynamic than Huarte to Snow. Ara consoled O’Brien that he would get plenty of snaps as the backup; this was prescient.

Purdue Game: A Strong Start

In came vaunted Purdue, brimming with confidence and eager for a shot at the Rose Bowl. The Irish took control early and pounded the ball to the Purdue goal line. But inside the 5, Rocky Bleier fumbled the ball; it was snatched out of the air by Leroy Keyes, and he waltzed 94 yards into the North End Zone. Purdue 7, Notre Dame 0. That took the air out of the crowd but did not deflate Ara’s Irish.

On the ensuing kickoff, Nick Eddy, large of heart and swift of foot, took the Purdue kick and ripped 97 yards for the game-tying touchdown. Hmmm! Twenty seconds, a 94- and a 97-yard scoring play!

The game settled in, and Purdue soon discovered the magic that Ara had watched on the practice field. In the course of completing 13 passes to Seymour for 276 yards, the Irish scored the next two TDs, both touchdowns by the gazelle, Seymour. But Purdue would fight, and Griese would lead the charge for one of only three offensive touchdowns scored against the Irish in ’65. With the issue not fully settled, Page rocked Griese on the pass rush, Griese coughed the ball up, and the Irish recovered and marched into the end zone on Seymour’s third TD pass. The Irish had a 26-14 victory.

Dominating Northwestern and Army

The following Saturday, Ara returned to his former lair in Evanston. He never lost a Notre Dame-Northwestern game from either sideline. Yep, he could “take his’n and beat your’n and take your’n and beat his’n.” The Irish dominated the yardage battle, 425-159, and racked up the first 35 points, giving up a garbage-time touchdown and winning 35-7.

That would be the last offensive touchdown the Irish would allow until the Michigan State game.

The Irish then returned to South Bend and rushed out to a quick 35-0 halftime lead against Army and cruised home with no points scored in the second half.

As ever, the media focused on offense, and Fling and Cling, Hanratty and Seymour, got a lot of ink. But the defense was crushing teams, like a python, first encircling an offense then squeezing it until it died. Good, clean violence.

Marching On: North Carolina and Oklahoma

The Irish continued their march with a 32-0 defeat of visiting North Carolina.

A rumbling was heard from the Southwest. Tenth-ranked Oklahoma was going to entertain the Irish. The Sooners were unbeaten at 4-0 and ranked 10th. They had dispatched Darrell Royal’s Longhorns 18-9. The Sooners felt their blazing speed and mercurial quickness would throw off the big, slow Yankees, and their quickness on defense with All-American candidate Granville Liggins, the nose guard, and speedy Eugene Ross would stifle the Irish offense. Well, this all got the Irish’s attention. In a brutally efficient performance, the Irish dominated, whipped, and shut out the hitherto unbeaten Sooners 38-0. The Irish had announced themselves as part of the national championship race.

The most anticipated regular season game in history

At this point, the country began to circle November 19th, Notre Dame at Michigan State. Oh, sure, Alabama was on its way to an unbeaten season, but it was playing in the segregated South, and the Tide even struggled to beat nondescript Tennessee 11-10. But it was the eye test that resolved it. Bama was small. Notre Dame and Michigan State were massive and swift. People who truly understood college football truly understood that it was Michigan State and Notre Dame, and then all the rest.

Several factors contributed to the frenzy surrounding the game. First, there were few games on TV, but this one would be televised.

Next, it was GUARANTEED that the game would be Michigan State’s last and the penultimate for Notre Dame, which had just the USC game after playing in East Lansing. The Big Ten played in only one bowl game, the Rose Bowl, and the Big Ten had a no-repeat rule. The Spartans had played in Pasadena the year before, so the mighty Spartans would be in no bowl game. Notre Dame was still under a 45-year hiatus from playing in bowls. This was a long time ago; the first Super Bowl had not yet been played.

The college football season would decide its champion on November 19, 1966. No ifs, ands, or buts.

Pro scouts fueled the frenzy. They were lining up to draft Bubba Smith and George Webster of Michigan State and Alan Page and Jim Lynch of Notre Dame. Michigan State, under Daugherty, recruited well in Chicago, Ohio, and Michigan but took advantage of segregation by dipping into the deep South for extraordinary talent. Bubba Smith was from Beaumont, TX, and receiver Gene Washington from La Porte. QB Jimmy Raye was from Fayetteville, NC, George Webster was from Anderson, SC, and Charley “Mad Dog” Thornhill from Richmond. Michigan State conceded NOTHING to Notre Dame in terms of national recruiting.

The Game of the Century

“The Game of the Century” label was attached early and repeated often. It “forced” the Big Ten to change its scheduling rules. The ND-Michigan State game was sucking the air out of the Big Ten season. The Ohio State-Michigan game, played the same day, was a page-three story in the sports section, including the big papers in Michigan. So, the Big Ten established a rule by which a Big Ten team could not play an out-of-conference game after the conference season started in October. That rule held until Penn State joined the conference, making it an 11-team conference still named the “Big Ten,” creating scheduling needs that trumped the “Game of the Century” rule.

The Irish continued to go through the schedule. They went to Navy and trounced the Middies 31-7, but did give up a TD on a blocked punt. Pitt came to South Bend, and the defense pitched another shutout, 40-0. Duke’s Blue Devils came in and were trounced 64-0. The first-string defense had not allowed a touchdown since the Purdue game. Eddy was the team’s leading rusher with 553 yards, followed by Conjar’s bulldozing 521 and 282 for Bleier. But it was depth that wore opponents down, and Haley, Gladieux, O’Brien, and Hanratty all rushed for more than 100 yards during the season.

Michigan State was unbeaten through nine games and had outscored its opponents 282-89. The Irish had outscored their foes 301-28.

As the train left South Bend for the short ride to East Lansing, well-wishers lined the train route with signs cheering the Irish to victory. As the train headed north, more of the signs shifted to Spartan loyalists with signs predicting Irish doom.

The doom predictions were partially fulfilled when Nick Eddy, nimble in California and South Bend, slipped on ice getting off the train in East Lansing and was out for the game. Nick Eddy could take a big hit, just not ice on a train platform. Interestingly, that was the last train ride the Irish team ever took.

November 19, 1966

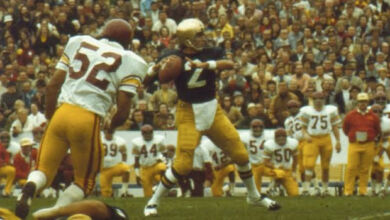

At last. The sky was Armageddon gray. The pregame warmups could have doubled as an NFL combine. In those days, the NFL had 26 teams. Seven first-round draft choices, more than 25%, in the ’67 draft would play in the game. Bubba Smith, Clinton Jones, George Webster, and Gene Washington of Michigan State and Alan Page, Paul Seiler, and Tom Regner of Notre Dame were the SEVEN first-round draft picks on the field. Larry Conjar and Jim Lynch lasted until the second round, Goeddeke and Rhoads the third.

Folks say it was the greatest amount of talent on both sides of any college football game ever played. And people who were there in the stands and who played agreed that it was the most physical football game ever played.

It was both modern in the size and quickness of the players yet a throwback because it was position/possession football with every yard contested with great violence and passion. It was bone on bone. The game was clean. Both teams were so confident of their power that they had no need to resort to penalties.

The game was epitomized by one curious but typical play. Jim Lynch, Johnny Ray’s on-field brain, made an exquisite drop and intercepted a Jimmy Raye pass. As Lynch galloped, somewhat, toward glory, he was body-blocked by All-America halfback Clinton Jones with such force that Lynch was literally flipped upside down, and when he landed on his head (were it an Olympic dive, it would have been described as a “perfect entry”), the force dislodged the ball. Sports Illustrated captured the moment in a photo: Lynch’s glistening gold helmet making contact with the Spartan green turf, the ball coming loose for a Spartan recovery.

Bubba Smith knocked Terry Hanratty out of the game in the first quarter. But Coley O’Brien had gotten a lot of snaps at QB, and he subbed in. Later, George Goeddeke injured himself on a punt play. Strength up the middle? Center Goeddeke, QB Hanratty, and HB Eddy were out! Ara never blinked.

As often happens in these epics, the scoring came from unexpected sources. Michigan State was able to muster one sustained drive on the ground. Early in the second quarter, Regis Cavender, the less famous of Michigan State’s Hawaiian running backs (Bob Apisa the other), punched in from the 5-yard line for a 7-0 Spartan lead. Later in the quarter, Dick Kenney kicked a field goal barefoot for a 10-0 lead. In this Midwestern classic, all points so far had been scored by Hawaiians. Were the Irish doomed? Parseghian, Pagna, and Ray didn’t think so.

Late in the second quarter, Pagna cleverly ran Gladieux from his RB position deep into the Spartan secondary, and Coley O’Brien was on the money for a 34-yard touchdown pass. Michigan State led at half 10-7.

The Irish had the better of it in the second half. On the first play of the fourth quarter, Joe “the Toe” Azzaro lifted the pigskin over the bar for a 28-yard field goal and a 10-10 tie. The slugfest continued, and the drama heightened. Tom Schoen’s second interception of the game gave the Irish field position, and Azzaro attempted a 41-yard field goal. He hit it solidly, but it was just inches right.

With about four minutes left, the Spartans got the ball but played it conservatively and punted, seemingly content with a tie. Ara and Pagna knew that O’Brien, a diabetic, had misfired on his last six passes. When the Irish got the ball back, they were on their 30, with just over a minute to go. After 58 minutes, the game had resulted in a tie, and that’s how it ended. Charley Thornhill, whose Spartans had just avoided risk in their last possession, barked at the Irish. But at that point, it was like talking smack at Joshua Chamberlain after his 20th Maine had secured Little Round Top at Gettysburg.

10-10. It was an elegant result for an elegant game.

Notre Dame at USC: Finishing Strong

The Irish had one game left, in the Coliseum against Rose Bowl-bound USC. Interestingly, USC and Purdue were the Rose Bowl participants.

O’Brien would be the Notre Dame quarterback in LA. The Irish received the opening kickoff and mixed in O’Brien’s passes to Seymour with the brutal running game, and the Irish pounded it in on a Conjar dive. Then, Tom Schoen returned an interception for a TD late in the first quarter for a 14-0 lead. At that point, the Irish had 9 first downs to just 2 for the Trojans. In the second quarter, Notre Dame’s dreadnought defensive line started dominating and smashed the USC blockers, accumulating big lost-yardage plays. The Irish added an Azzaro field goal, then two gliding touchdown catches from Jim Seymour to post an insurmountable 31-0 lead at the half. Coleman Carroll O’Brien would finish with 21 completions in 31 attempts for 255 yards and 3 TDs. The game would end in a 51-0 romp on an afternoon when Michigan State could only watch as their season was concluded.

National Champions: The Era of Ara

The Irish vaulted to a commanding lead in the AP Poll and were the National Champions. The Bowl Games, more or less, were a loser’s bracket. Purdue won a thriller over USC in the Rose Bowl, 14-13. Michigan State and Notre Dame had outscored the Rose Bowl participants 118-35.

A fancy-dan quarterback from Florida named Steve Spurrier won the Heisman Trophy. Clinton Jones, Regner, Page, Lynch, Bubba Smith, and George Webster were All-Americans.

Ara had his national championship, the first in 17 years, since Leahy’s last in ’49.

The era of Ara was here!

Go Irish